Everything Grows from the Heart

By Amy Sellors

The challenges of the past two years have shown us that art helps us heal. Anishinaabe artist Tom Tom Sinclair knows this well. “Art helps me see the world in a good way, in a colourful and beautiful way. Especially now, during the pandemic, where everyone is so separated from each other,” he says. “In my art, I show connections, things on a spiritual level. That’s why I often put strawberries in my paintings—ode’imin—heart berries. Everything grows from the heart.”

Anishinaabe artist Tom Tom Sinclair with his painting The War Party

Credit: The Canvas Gallery

Sinclair’s mom is a survivor, and his family has been through a lot. He’s worked many jobs, but none of them gave him any sense of satisfaction or mental well-being. As a truck driver he drove across North America. “The destruction I saw from forestry and mining and pipelines, and seeing all of the accidents—I had PTSD. I retired at a young age; I quit everything. I did counselling, therapy, I tried it all. I worked my tail off to get where I am. Art saved my life.”

Growing up in Thunder Bay, Sinclair’s father was an addiction counsellor. He would drive the streets and sometimes pick someone up who needed help and bring them home to sober up. In the morning, over tea and toast, they’d see Sinclair drawing. One of these men especially influenced him: the artist Isadore Wadow. “He showed me so much about Woodland Art, what the symbols are, what they mean, and where they come from. He showed me how to harvest onaman—the sacred sand—and to use it to make traditional pictograph paint.” Sinclair is one of the few people who still has the original “recipe” for this paint and who knows how and when to harvest the ingredients. Wadow was murdered in Thunder Bay in June 1984, and Sinclair stopped painting for 30 years.

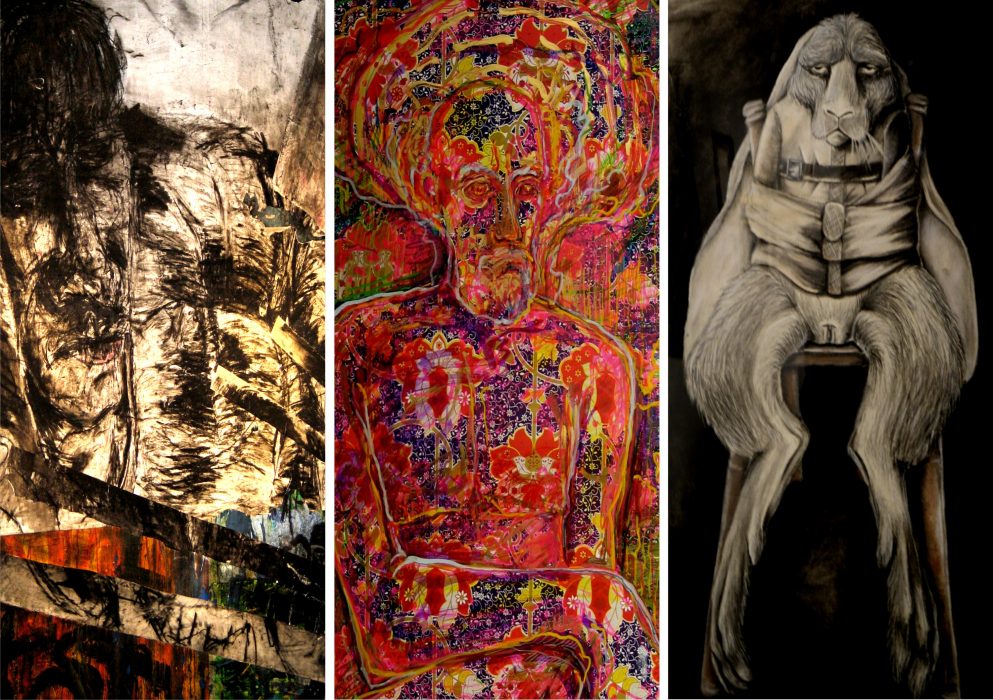

The Shapeshifter vs the Trickster

“After Wadow was killed, other Indigenous artists told me that Woodland Art wasn’t safe. It all had to do with the Norval Morrisseau fraud ring. I only made art for myself after that. Once a year I would buy a canvas and paint.” In time, art became a part of Sinclair’s healing. “It was helping me to find pride in myself. Making art helped me find pride in being Anishinaabe again.”

Sinclair’s art is on display around the world, and he is working on pieces to show in Milan, Madrid, Venice, Toronto, and Montreal. While proud of his accomplishments, this wasn’t what he envisioned. “I wanted to sit at my mom’s table and paint pictures for her friends and family. This is all a little scary.” And while scary, he knows how important it is to share Indigenous culture. “A lot of Europeans aren’t even aware that we are still alive—that we still exist. We are showing them that we’re still here, still practicing our culture, and trying to save our languages for our grandchildren and their grandchildren.”

Currently, Sinclair’s home is Sault Ste. Marie, where he’s working to open a studio. “All of the greatest artists in Canadian history have created here. It changes people. The colour palette, the imagery… I can’t explain it, but that’s why I live here. Within a half hour drive, there’s almost every type of landscape.”

Healing

With tears in his eyes, Sinclair confides how important it is to share Indigenous art. “I want all my people to feel this way. The more I paint, the less afraid I am to bare my soul to people. For me, each individual is on their own journey, whether it’s destruction or healing. There’s always a spiritual way of looking at things, a spiritual way of existing,” he says. “In my paintings, I often put three orbs in a line. They represent unseen spiritual connection, communication, and relationship. That’s the only thing I am trying to say in my art—we’re all connected, we’re all one.”

Follow Sinclair on Instagram and Twitter @tsinclair76.