By Michelle McChristie

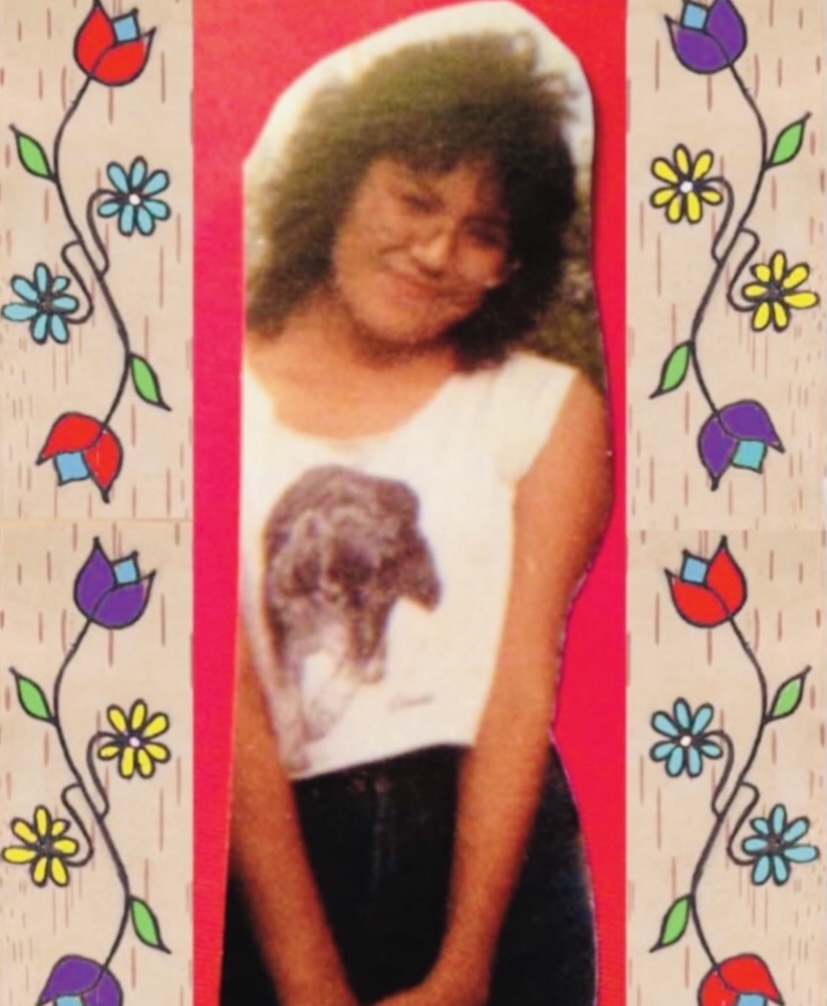

Sandra Johnson was only 18 when she was murdered on February 13, 1992. Her body was found on the frozen Neebing-McIntyre Floodway, close to where her sister, Sharon, returns every year to lay tobacco.

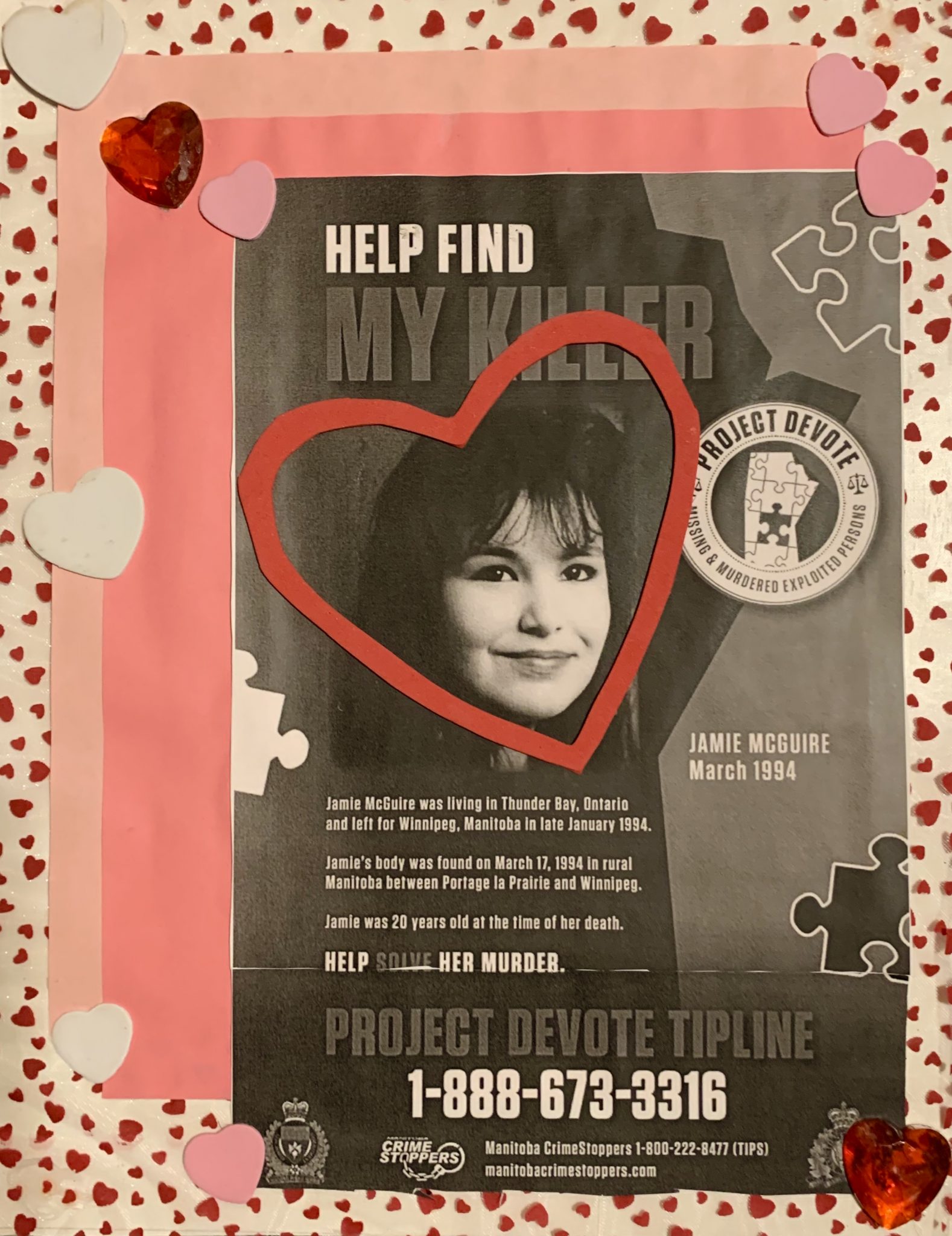

In the years that have passed, Canadians have come to learn that Sandra’s case was far from an isolated incident. In 2019, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls’ final report revealed that “persistent and deliberate human and Indigenous rights violations and abuses are the root cause behind Canada’s staggering rates of violence against Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people.” The report called for transformative legal and social changes to resolve the crisis that has devastated Indigenous communities across the country.

A photo of Sandra Johnson that her sister, Sharon, has carried for many years

Sharon Johnson acknowledges that the level of public awareness of violence against Indigenous women has increased. “When it happened to my family in 1992, I didn’t really see anything in the news—it wasn’t talked about. I first started hearing about these issues from the Native Women’s Association of Canada when I was a university student in 2005.”

Back then, Amnesty International’s report cast a spotlight on discrimination and violence against Indigenous women, but Johnson recalls it was “only the report that was in the news.”

In 2007, Johnson organized Thunder Bay’s inaugural Valentine’s Day memorial walk for MMIWG (missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls). The memorial walk is based on an event that was started in Vancouver in 1992—the year Sandra was murdered. Every Valentine’s Day, thousands of people gather to honour the lives of that city’s missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Three years ago, Johnson passed the reins to Kim Ducharme, a professor in the Child and Youth Care Program at Confederation College. Ducharme feels strongly that practitioners need to understand what is going on in communities and how it affects youth. As a non-Indigenous woman, she hopes “more settler participants recognize it’s a national issue.”

Ducharme, with help from guest speakers, takes her students through national and local reports that document the impacts of colonization on Indigenous people, systemic discrimination, and intergenerational trauma. “The class culminates with the memorial walk—it’s a way for students to share their commitment to taking action,” she says.

Kim Ducharme and Sharon Johnson

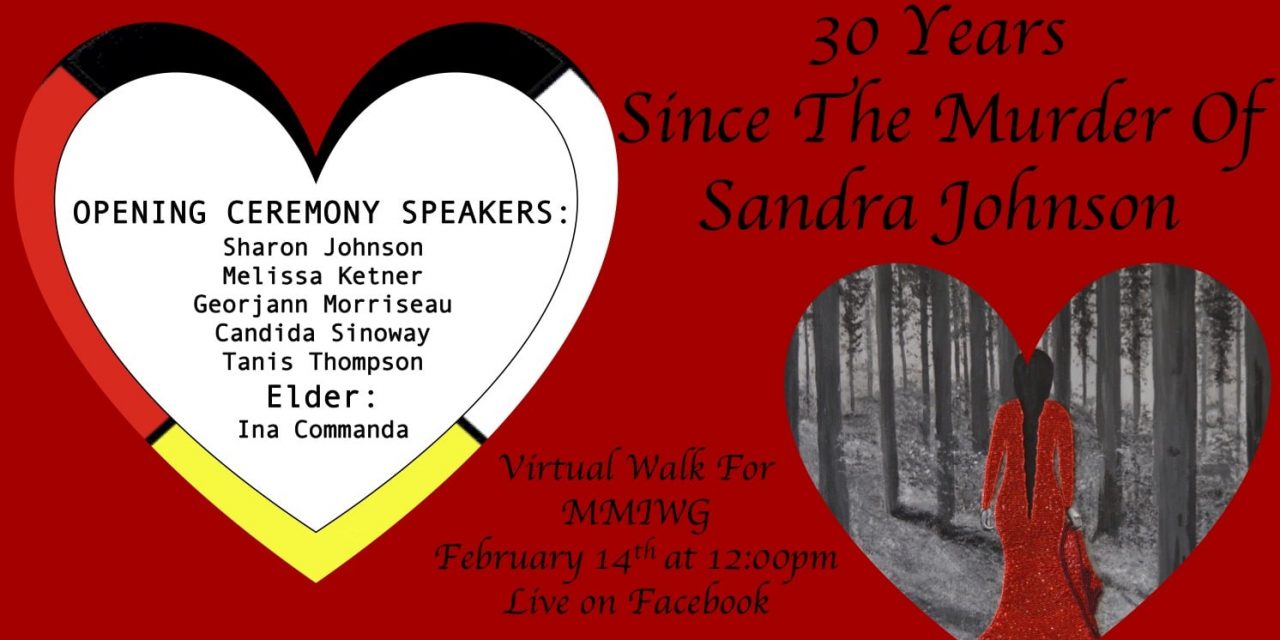

Due to uncertainty around COVID restrictions, this year’s walk will be held virtually on Monday, February 14, 2022. The opening ceremony will be live-streamed at noon, led by Elder Ina Commanda, and including remarks from Melissa Ketner (sister of the late Barbara Ketner), Candida Sinoway (a student in Confederation College’s Child and Youth Care Program), Georjann Morriseau, Tanis Thompson, and Sharon Johnson.

Participants are encouraged to take a picture of themselves walking in the community to honour MMIWGMB2S, post on the Facebook event page, and encourage others to do the same.

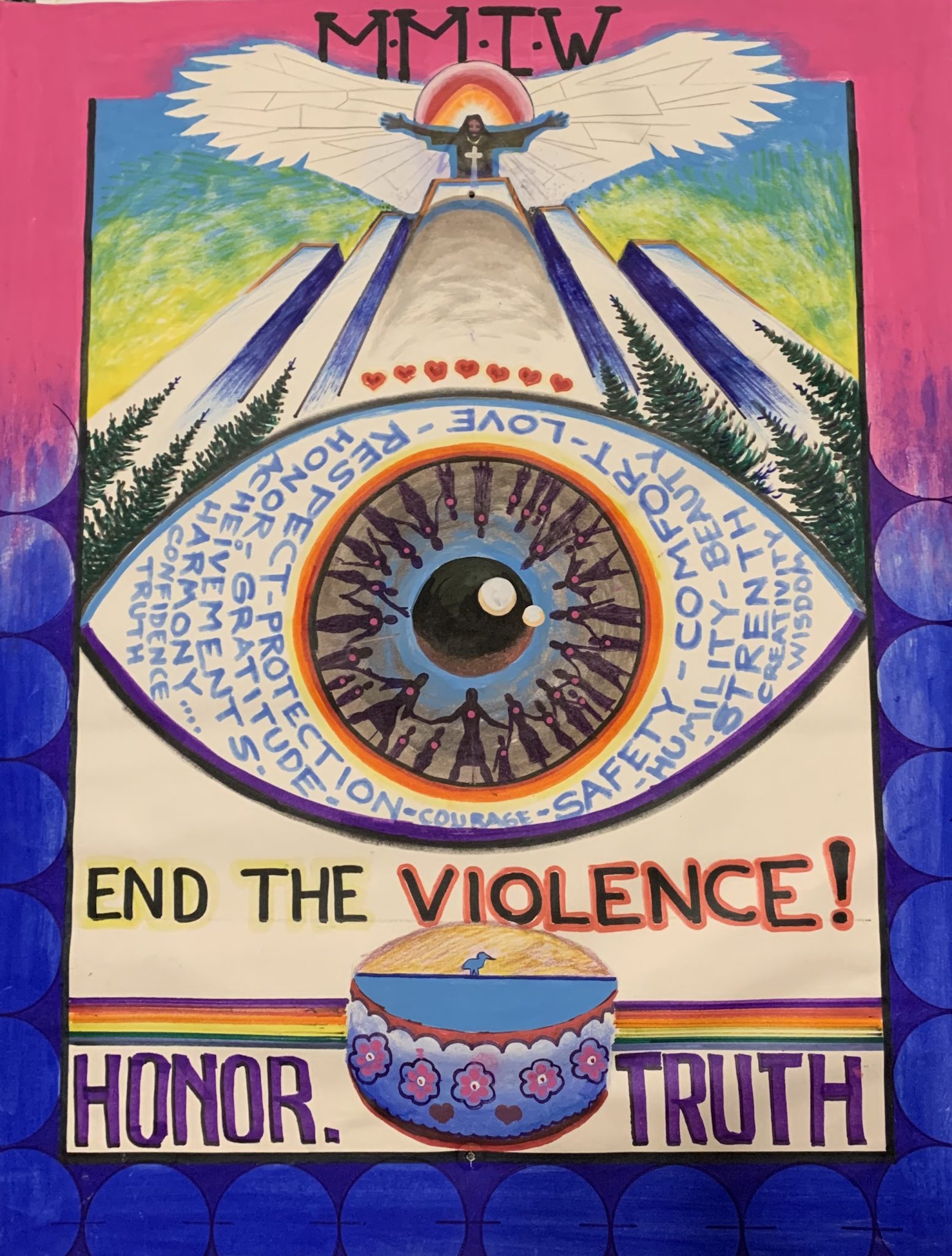

- A poster made by Perry Perrault

- According to Statistics Canada, Indigenous women 15 years and older are 3.5 times more likely to experience violence than non-Indigenous women

- A participant carries an eagle staff; this photo is from an earlier walk when the route ended at the CLE Heritage Building

- Event participants walking along Simpson Street

- A Valentine’s Day heart and a tobacco tie—in the past, event participants gathered to create heart pins and tobacco ties