By Justin Allec

Larger than life. A legend in his own time. A hillbilly, a rocker, a lover, a fighter, a father, a songwriter beyond compare, Steve Earle is all of these tags and much more. With his latest album So You Wanna be an Outlaw? going steady on the charts and a lengthy tour ahead, including a stop in Thunder Bay at the Thunder Bay Community Auditorium on September 24, Earle, even in his early 60s, is doing what he loves for some very good reasons.

The Walleye: Given everything you’ve been through—addictions, marriages, bankruptcies, living as a touring musician—what does being an outlaw mean to you today?

Steve Earle: It means what it always did, but it’s also about rehabilitating that term. A lot of people that weren’t there when outlaw country came out thought that it was about lifestyle, but it wasn’t just that. It was about country artists figuring out that rock artists had more artistic freedom, and they wanted to do that, to make the records that they wanted to. And I was there, and that’s what I always did, always trying to make the best records that I could. That was my calling and I did whatever it took to get them made.

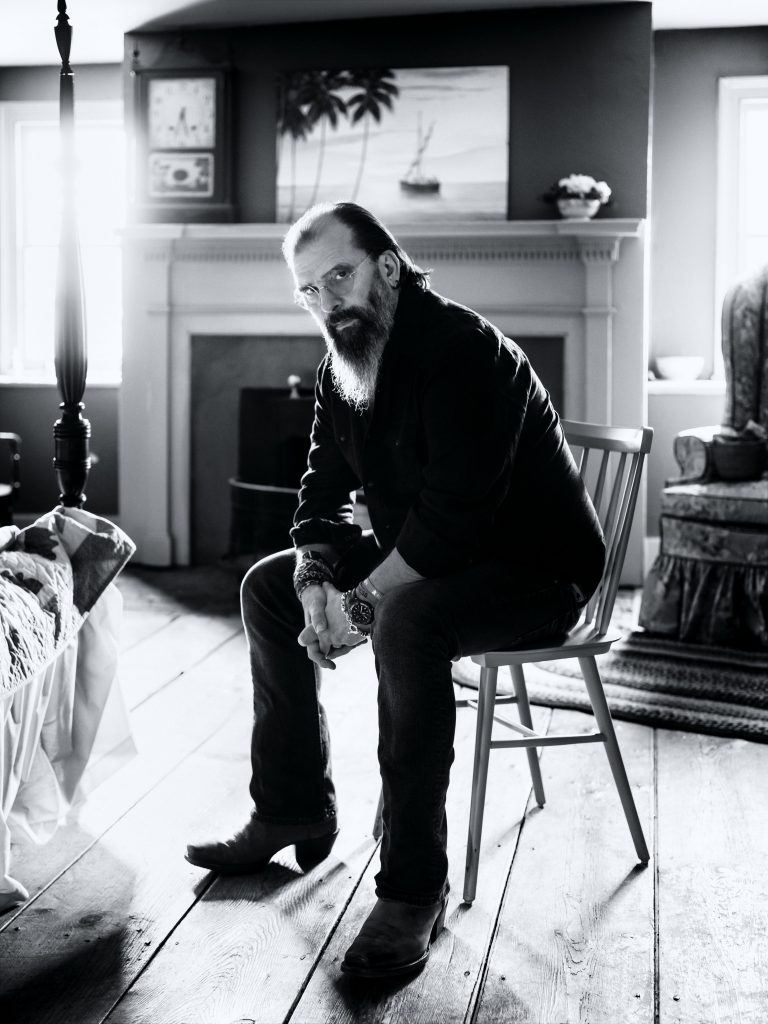

American singer-songwriter Steve Earle, photographed at Dyckman Farmhouse in New York. Photo by Chad Batka.

TW: After a few passion projects the last few years, this record seems to be a return to hard country, hard rock. What was the motivation there?

SE: Well, you gotta make a record about something, you know? I mean, I’m writing a memoir, so maybe that prompted a bit of it, but a lot of it had to do with timing. I was asked to write a song for the TV show Nashville, “If Mama Coulda Seen Me,” which got used in the first season, then in the second season they also asked me for another song…so I wrote “Looking for a Woman,” which gave me two songs, then I went on to make the blues record (Terraplane) and the record with Shawn Colvin (Colvin & Earle), then in the middle of the Colvin tour it occurred to me that I’ll have to make another record, cause I got alimony money to pay, so I got the songs out, dusted them off, then they seemed to fit together well enough, then I realized—I’ve been listening to a Waylon Jennings record, Honky Tonk Heroes, about every few years whether I need to or not—but maybe that’s what this record will be.

TW: You mention Waylon as your hero, but here on the first song on the record you’re going toe to toe with Willie Nelson. You gained more prominence in the 80s after a lot of those outlaw heroes, but now you’re standing equally with them…

SE: Well, I came up at the same time, I started making records then, but I got to Nashville when I was 19 right in the middle of all that, and the window closed, and I didn’t get a record deal in time. But that’s still what I’m about, what the record means.

TW: Do you see yourself as being remembered as part of that group: Waylon, Willie, and Steve?

SE: Oh yeah, I always have. That’s just how I came about as an artist.

TW: Not sure if you know, but classic rock radio will play “Copperhead Road” about twice a day. That song’s pretty awesome and a great gateway into your vast catalogue. Do you still play that song? Do you like it?

SE: Yeah, we still play that song every night. There’s three or four songs we play every night—“Copperhead Road,” “Guitar Town,” “The Galway Girl”—and there’s some songs you just have to play every night, and I’m okay with that. I still get something outta playing them, the fans love them, and why would you not be proud of a song that connected with a lot of people? That’s not a reason to not play a song… to me that’s a reason to play it every night.

TW: So what makes a good song to you? What makes you say, “Yeah, people have to hear this”?

SE: A good song lets you find what you have in common with the audience—you’re no different from anyone watching you play. Everybody loves, everybody misses their kids, everybody celebrates, those are the things that people relate to in songs, so those are the good ones. This job is about empathy as much as anything else. To me, good songs make people feel like they’re not alone, and that someone else feels like they do.

TW: Is that one of the reasons you’re still touring?

SE: Well, that and I have to make a living. I can’t afford to not tour. I need the money, so… I mean, I like to tour and it’s a good thing I do, cause I don’t have a choice. There’s no real record royalties anymore and I’ve been married a lot, so I don’t really have any money, so I just have to keep working.

TW: Along with all that, you’re a father. Your son, Justin Townes Earle, is coming into his own as an artist, and you have another son who has some unique challenges. How does that influence your life?

SE: Justin’s doing real well, and he’s got a little girl now who I just met, and she’s like six weeks old, and my middle son has kids, so I have three grandchildren. My youngest son, John Henry, is seven. He has autism, and kinda everything I do now is for him. I think he’s gonna be fine, but I want him to be well, and it costs money to get him the care that he needs to give him the best chance that he possibly can. He’s doing better than a lot of kids with autism cause he lives in a place where he can get those services, in New York City, and I make sure that he gets them. He’s the main reason I wake up in the morning every day.

TW: You’re working really hard but you’re also famously clean. What defines a good time for you now?

SE: Baseball and live theatre. Those are two things that I really love—oh, and fishing with a fly rod, which I’m gonna do tomorrow in Idaho. The rest of the band will wait for me , I’ll buy them a steak, then we’ll play Billings, Montana. We get a break in a few weeks and I’ll take John Henry to the beach.

TW: It’s hard to ignore that there’s a lot going on in your country now. You’ve been an activist, but you’ve also written some songs from some contrary perspectives. Are you getting more material out of all this, or do you just want to leave the country?

SE: I was in Canada the night Trump was elected. I was playing in Ottawa on the Guitar Town 30th Anniversary Tour, and we didn’t know this was going to happen. It blindsided everybody. I wrote this record thinking that we were going to elect Hillary Clinton. She wasn’t my favourite choice, but I voted for her, and I thought I’d walk off stage and find that we’d elected the first woman president, and instead I find out we elected the first orangutan president. People have asked me why the record isn’t more political, but most of the songs were written before all this happened, so I decided to just let it be what it is, and the next record will be just as country as this one, but way more political.