How High School Music Classes Have Adapted to COVID-19

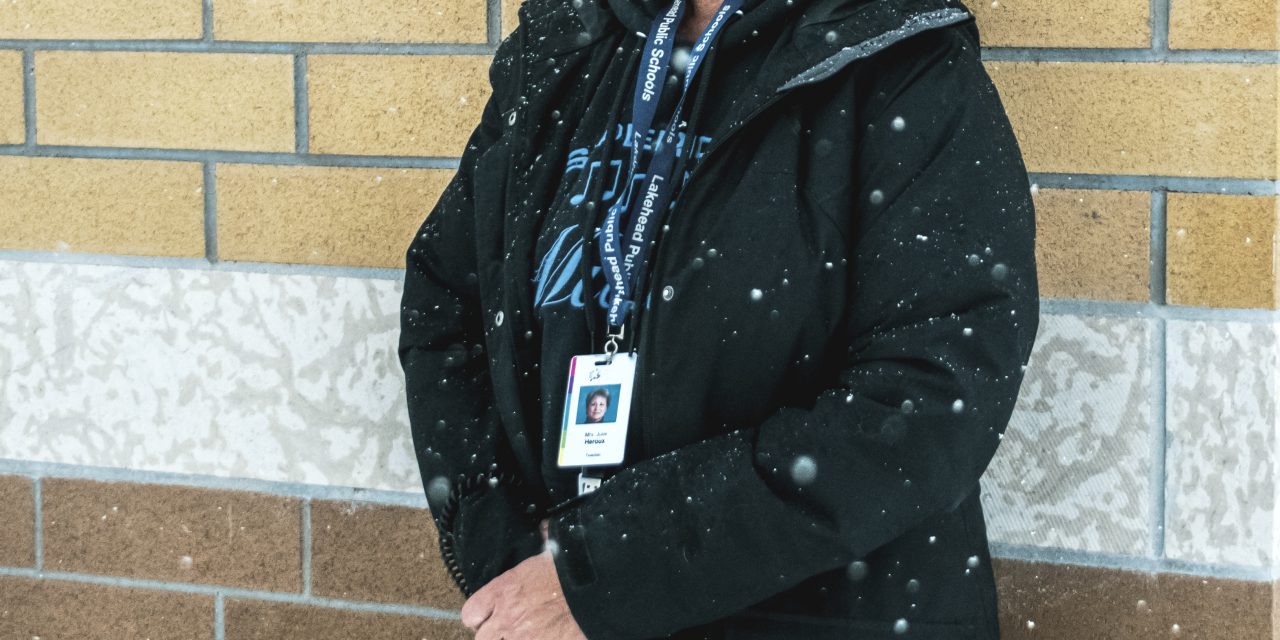

Story by Matt Prokopchuk, Photo by Keegan Richard

If you were a high school music student in a pre-COVID world, showing up to class or after-school rehearsal and practicing with dozens of your peers was something you could take for granted. But, as the pandemic has forced major changes to virtually all aspects of life, students and teachers in the city’s highschools are rethinking those lessons.

Lakehead Public Schools says all of its traditional music classes have been able to run this school year, but with modifications. That effectively means there’s no practising or performing of wind instruments (including all woodwind, brass, and percussion) or singing while classes are in-person—that instruction is only done virtually. In-person classes, the board says, are dedicated to string instruments, including guitar, as well as music theory, history, and other disciplines. For music teachers like Superior Collegiate & Vocational Institute’s Julie Heroux, it means doing things very differently these days. “That has been a real challenge,” she says. “For example, I have a repertoire class, which is concert band, and that course I’m delivering as a completely online course.”

While technology has allowed many facets of life to migrate to virtual spaces, Heroux says that doesn’t extend to playing as an ensemble. “The platform that we use doesn’t synchronize the sound waves enough to allow for students to play together,” she says, adding that where the technology has been very useful is in creating what she calls “breakaway spaces.” Those act as virtual closed studio spaces where she can, during online classes, separate and provide rotating instruction to smaller groups based on instrument or experience and skill level. “It’s a lot of me hopping from one designated space to another and meeting with all my kids,” she says.

Heroux adds that she’ll also schedule 30-minute virtual sessions with students outside of school hours to provide individual instruction (even during normal times, concert band is held after school). “Even though it’s tough to deliver a program like this, it can be done,” she says. “But I think it’s really important that I do it, because that way my students can feel they’re making progress on their instruments and they feel like I’m able to give them [the] attention they need that’s specifically designed for what they need on their instruments.” Focusing more on solo repertoire with the students, rather than exclusively working on music that’s designed to be performed as part of an ensemble has also made the current format work more smoothly, she says.

And even with live ensembles on hold, there are still ways to simulate that experience, Heroux adds, including giving students access to a recorded piece of music with their individual part missing. “The student plays along with the recording,” she says. “So it makes it as close to an ensemble feel as it can be.”

Even though the current model is challenging, Heroux says, it has opened up new ways of doing things—some of which will likely outlive the pandemic, including offering virtual spaces for individual instruction outside of regular classes for those who want to use that method. And at the end of the day, Heroux says the most important thing is that students still have a chance to play. “It’s wonderful that we were able to offer music, given the pandemic,” she says.