Thunder Bay Literacy Specialist Calls for More Attention to Learning Disabilities

By Matt Prokopchuk

A literacy specialist in Thunder Bay says more attention needs to be drawn to invisible learning barriers like dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and that more help and resources need to find their way to help those who have the conditions.

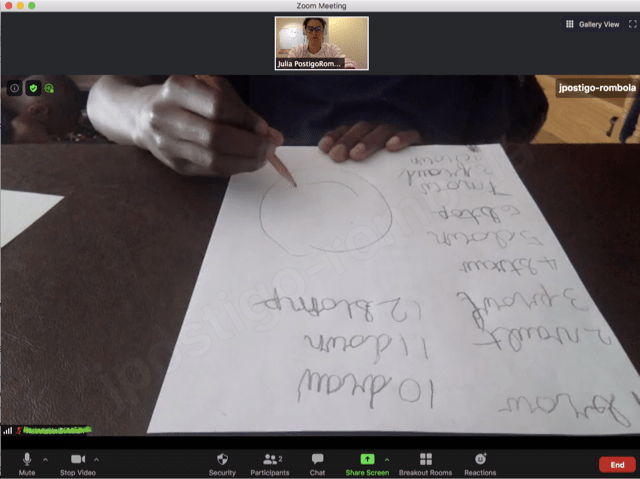

Julia Postigo-Rombola, the owner of Naturally Literate, a literacy centre in the city, says stigma and a lack of understanding around these barriers can lead to children being unfairly and wrongly criticized and mocked for being lazy or lacking intelligence, which then can lead to low self-esteem and mental health issues. And that’s on top of the challenges to learning they already deal with.

“Dyslexia is a language-based barrier, it has nothing to do with [intelligence], like your IQ,” Postigo-Rombola says. “It has to do with processing information from a page to your mind, or from your mind to a page; it has nothing to do with comprehension.” Dyslexia can manifest itself in many ways, for example, a person verbalizing “b” as “d” or “m” as “w” (or vice versa) when reading; similarly, people with dyslexia may speak a whole word in reverse (such as saying “god” when the word on the page is “dog”), even though they fully comprehend the difference. Letters may appear jumbled, or students may have trouble connecting letter symbols with sounds. These challenges aren’t uncommon either, with dyslexia being the most prevalent type of learning disability, according to the International Dyslexia Association, with as many as 15–20% of the population nationally having at least some of the symptoms.

Aside from working with young people who have challenges with literacy, Postigo-Rombola knows of them first-hand, as she has dyslexia (as well as dysgraphia, another condition that affects handwriting) and ADHD. The latter, she says, makes learning difficult as the mind never ceases racing, making concentration very difficult, even if the person is outwardly calm. Frustration at not being able to process these learning tasks can easily take hold, she says, and there can be wait lists for the necessary assessments for the child to receive specialized help.

“When I was learning to write in grade four, for example, I would write my “j’s” backwards, and it’s my name,” she says. “It didn’t matter that I knew how to write it—I could see it, I could recognize that that’s a ‘j’— but I kept flipping the ‘j’ the other way. And it’s like 15 days in a row and I see those 15 failures in a row and it’s just like ‘give up, rip the paper, scream, storm out the door,’ because it’s so frustrating.”

Ontario’s human rights watchdog has also taken notice, as it is in the midst of a probe into whether the province’s public education system is meeting the needs of students specifically with reading disabilities like dyslexia. The Right to Read public inquiry by the Ontario Human Rights Commission, which is expected to produce a report in spring 2021 containing detailed findings and recommendations to government and education stakeholders, held public hearings in four Ontario cities, including Thunder Bay prior to the pandemic, along with soliciting feedback through numerous other methods.

Overall, Postigo-Rombola says she fears that kids are “falling through the cracks,” especially with the pandemic-era shift to remote and virtual learning, and wants people to know there are services available for professional help and advocacy. “It’s really challenging for families,” she says. “When I work with families, it’s a lot of emotional support for the families too.”

For more information, visit naturallyliterate.org.