By Lindsay Campbell

Since it made its debut last October 22, 2018, the Canadaland podcast series, Thunder Bay, has received national attention for the stark spotlight it shines on the city. This month, The Walleye had the chance to speak with Ryan McMahon, creator, writer, and host of the project, to ask him about the five-part series.

The Walleye: What’s the reaction been like from residents who have heard the podcast?

Ryan McMahon: It’s been overwhelmingly positive. We were proud to have had the green light from so many journalists who had worked in Thunder Bay and who had worked on some of these stories before. One of the first things we did was let them know what our intention was, and you’ll hear many of their voices throughout the series. You’ll hear Jon Thompson, Willow Fiddler, and Tanya Talaga, and we talked to many other journalists who wanted to remain off the record for a number of reasons. But we were very proud of the fact that people gave us the thumbs up in terms of having the chance to build off of their work. I think there’s a number of reasons for that, one being that it’s a podcast. The power of audio storytelling and the intimacy of the podcast genre allows the story to be told in new and different ways. When you can hear the pain of people and not just read it or glance at a headline or scroll past it on Facebook, but actually hit play on a podcast and listen, it brings a level of intimacy that I think is missing from other mediums. We were allowed to present a lot original reporting through this medium as well. I think there’s been some push back from people and there has been some response that we’ve only focused on the negative and that there’s so much more to talk about in Thunder Bay. But, frankly it’s not the positive stuff that’s killing Indigenous youth in Thunder Bay. It’s the problems that we seek to shine a light on through the series that we need to talk about. News of the young Jacobs boy who was found in a park really brings out the fact that we did what we were motivated to do. We did what we had to do and if we had a do-over we would do the exact same thing over again.

TW: What was the hardest part for you doing this series? What did you find the most challenging?

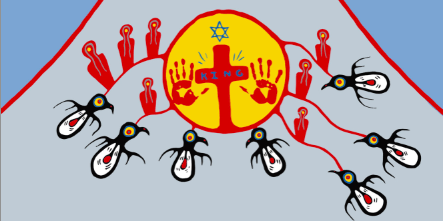

RM: Easily the most challenging thing is having the voices of Indigenous youth stuck in my head. The voices, the stories, the experiences of young people who were just born into this country that hates them, and they have to experience that for no other reason other than they’re Native. To know that they genuinely feel fear when they leave the house and that they genuinely believe that something bad could happen to them any given day because they’re in Thunder Bay is a constant source of sadness for me. I will repeat again, this is not an indictment on Thunder Bay, but it’s an indictment on some of the people in Thunder Bay. When I say that these kids feel fear, they’re not making it up. They don’t want to feel that. They don’t want to think about being killed in that city. They don’t want to be vulnerable. There’s a very, very poor system that ensures they feel that. It’s just a tough pill to swallow that we’re still in this place in 2018 where we are debating whether or not racism is real or whether the Indian Act or any other act for that matter is worthy of change or not. I’m really frustrated that we’re still having those debates.

TW: You mentioned in the podcast that Thunder Bay operates under a broken system. Now that Keith Hobbs is out of the picture, what’s going to happen with a new mayor?

RM: Well the first public statement that Bill Mauro made, to Steve Paikin, was doubling down on the idea that Thunder Bay just had “bad publicity.” We included that clip in the podcast, where Mauro says he’s going to fix the reputation of the city. Not fix the city, not fix the services, not find ways to bolster the organizations or services inside of the city, not work with the province or with NAN [Nishnawbe Aski Nation] or with the Friendship Centre to make the city safer, not do what the Thunder Bay Bear Clan [Patrol] is saying to do. Instead, he’s going to fix the reputation. So, no. He’s saying what Hobbs has already said for eight years, and to say that’s a disappointment from my perspective would be putting it lightly. I think that statement, should he stand by it in the future, lacks empathy, lacks leadership, and is cowardly. I want to be on the record for saying that. He’s a professional politician and people love this guy—I’m sure he knows his way in and out of a political meeting, but maybe he doesn’t get the depth of the challenges. Or maybe he does and he’s just trying to put people at ease. But this is what I think is so fundamental: if someone on the inside said ‘yes, we need help,’ then I’d bet Thunder Bay would receive the help it needs. I think everyone knows what’s happening in this city, but someone just needs to say it. It’s going to take vulnerability, compassion, and empathy, and it’s going to take standing up to the base in Thunder Bay. I think the base in Thunder Bay thinks that things are fine and that employment and infrastructure and crime are the core problems, but I don’t know if the base in Thunder Bay believes that wholesale change is necessary. But I was hoping that Mayor Mauro would show a different type of leadership.

TW: Throughout this podcast we hear from people who have been victims of racism in Thunder Bay. Have you had criticism about the lack of sources from the police people or city council?

RM: Yes, we have received that criticism and people should know that the mayor, city council, Thunder Bay Police [Service], NAN—none of them would talk to us. We wanted to give people the opportunity to clear the record. We told them what we were doing and we said we were going deep and it’s going to be felt. We finally got an email back from Mayor Hobbs the day before we were publishing our final episode, and it was basically him slapping threats of libel on us and that’s all we ever heard. Premier Kathleen Wynne, Jane Philpott, Carolyn Bennett—I could list people that didn’t want to talk to us. We fully intended to include all views, but at some point in your process, you do have to look at what you actually have and try to tell the story with that. That’s the truth.

TW: What do you hope to achieve from having people listen to this podcast?

RM: I hope they understand how the city of Thunder Bay got to this point. It’s not even Thunder Bay’s fault. It’s not necessarily all of Mayor Hobb’s fault, it’s not city council’s fault. There’s a whole bunch of ways the city of Thunder Bay got to be the way it is. This is to not let anyone off the hook. There is a failed system—or, I would say a successful system that has ensured that Indigenous people rely on Canada. It’s either working exactly as it was designed or it’s broken. I believe it’s working—the system was never meant for Indigenous people to thrive. There’s a lot that needs to be done politically and I believe the answers are in front of it. The big issue is the paternalistic nature of the government. But then what will be necessary to get to the point of change? One of my goals was to contribute to the re-education of Canadians about the failings of the government. The recreation of this country was a business deal. Part of the deal was that this country would provide the same education for Indigenous people as non-Indigenous people. This country has failed to do that and we wanted to make a podcast that shows what that looks like and what it means. Looking at why Thunder Bay is the way it is and the failure of the system were the explicit goals. This story could have taken place in a lot of other different cities, but we landed on Thunder Bay cause that’s where I’m from.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.