What the Finlandia Hall’s Heritage Designations Mean for Buyers

By Matt Prokopchuk

The eventual buyer of the Finlandia Hall in Thunder Bay will have to navigate some rules and regulations surrounding the preservation of the building’s heritage features, according to the chair of the city’s Heritage Advisory Committee, but restorations of other local historical buildings show how that can be done.

The Bay Street property has been officially listed for sale for $599,000 as part of the liquidation of the Finlandia Association, which was the organization that owned and operated the hall—also called the Finnish Labour Temple—as well as the Hoito, which was housed within. The association’s membership voted in May to liquidate so it could settle over $1 million in debt. A local cooperative is among the parties interested in purchasing the hall.

The building has been designated a national historic site through Parks Canada and a plaque out front commemorates the site’s place in Canadian history. Aside from that, however, federal officials say their designation doesn’t do much in terms of prescribing what the building’s owner can or can’t do, should they decide to renovate.

The building has been designated a national historic site through Parks Canada and a plaque out front commemorates the site’s place in Canadian history. Aside from that, however, federal officials say their designation doesn’t do much in terms of prescribing what the building’s owner can or can’t do, should they decide to renovate.

“The designation of national historic sites is honorific in nature,” Megan Damini, a media relations representative for Parks Canada—the agency that oversees Canada’s historic sites—said in an email to The Walleye. “While a national historic designation helps to focus public attention on a particular site, it does not affect ownership of the site or provide protection against interventions, as these matters are the responsibility of the provinces and territories under their respective heritage legislation.”

She added that Ottawa has little authority over privately-owned heritage buildings, other than to encourage owners to consult heritage conservation experts whenever planning work on a historical site.

“No permissions are required from the federal government for work, interventions or the sale of national historic sites that are not federally owned,” she says.

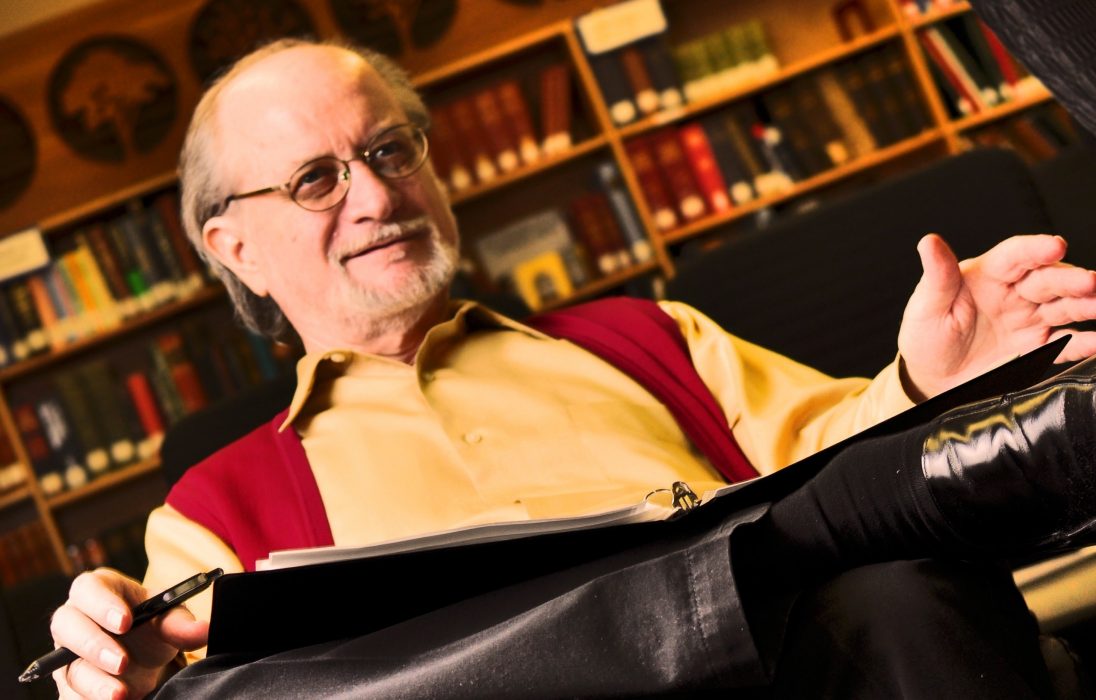

There are protections, however, offered by the Ontario Heritage Act, which allows cities to flag properties in a couple of different ways, says Andrew Cotter, the chair of the Heritage Advisory Committee. That includes placing properties on a heritage registry or designating a property as a heritage site. The latter, Cotter says, brings many more rules into play for renovating such a site; the Finlandia Hall has been formally designated.

“Any time they pull a building permit, it would get flagged to the Heritage Advisory Committee for review and approval,” Cotter says. “Our committee would work with the owner and make sure that [any proposed renovation] meets the provincial requirements for protecting heritage elements of a building.”

That effectively protects the building from demolition or major renovations that would destroy the building’s unique features, however, significant work can still be done. Other provincial laws, such as those under the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, may also require upgrades to a property, such as installing elevators, Cotter says.

“We work closely with any owners to make sure that … they comply with protecting the heritage elements.”

The committee’s role, however, isn’t to impede a building owner from repurposing a property to be viable in the modern day, Cotter says.

“When we have these buildings, and they do, unfortunately, sometimes suffer these fates where they’re very large, they’re very difficult to maintain, and costly to maintain,” he says. “A lot of these buildings in their present form—business form—are just not viable assets.”

When that happens, Cotter says, the committee is open to what’s called “adaptive reuse,” meaning changing the function of the building without destroying its heritage value. Most times, he says, the consultation process between the committee and owner keeps the heritage elements intact. A recent example in Thunder Bay, he says, is the Courthouse Hotel on Camelot Street.

“Adaptive reuse is always the best option for historical buildings, rather than having it sit empty [and] have a heritage advisory committee stranglehold, basically, on a given asset,” he says. “Then it will suffer demolition by neglect.”

“We always take the avenue of adaptive reuse and work very closely with the owner.”