Story by Michelle McChristie, Photos by Sarah McPherson and Betty Carpick

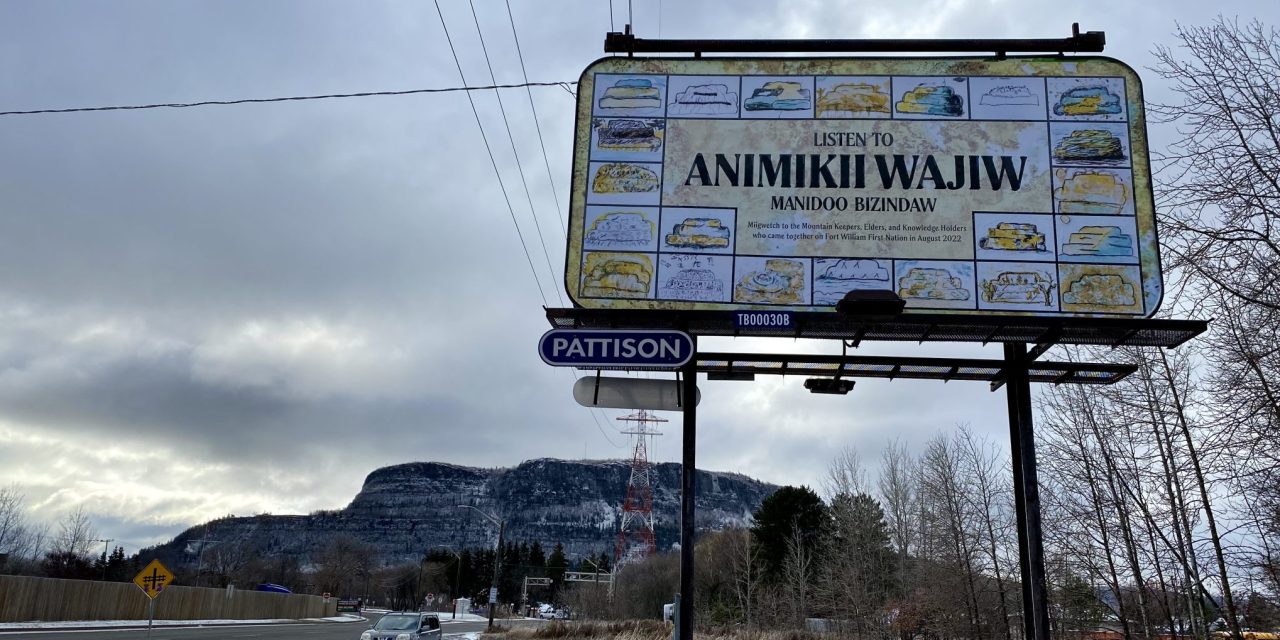

Earlier in November, a billboard featuring 22 artworks made from natural inks made from plants and water gathered on Animikii Wajiw was installed along James Street South near Kingston Street.

“The billboard invokes a bit of curiosity,” says artist and environmentalist Betty Carpick who conceived and led the project that culminated with the art, billboard, and call to action. “Some people aren’t familiar that Animikii Wajiw is the Anishinaabemowin name for Thunder Mountain or Mt. McKay. The billboard’s location is strategic—people will see it on their way to Fort William First Nation.”

In August, participants from Fort William First Nation’s Mountain Keepers Youth Program, Elders, knowledge keepers, and the Climate Change and Health Adaptation program explored past, present, and future relationships to place and environmental stewardship using handmade art materials.

The Mountain Keepers Youth Program is guided by Gail Bannon and supports teens who work as summer caretakers on Animikii Wajiw while strengthening traditional knowledge and skills. The Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program is a collaboration between Fort William First Nation and Lakehead University and supports a focus on human health within a changing climate. The project is guided by Dr. Lindsay Galway, Canada Research Chair in Social-Ecological Health and associate professor at Lakehead University, and supported by Courtney Strutt and Elizabeth Esquega.

Youth collected goldenrod and speckled alder, two Boreal Forest plants, and water from natural springs on the mountain. The collection of plants and water was done with respect to tradition, abundance, and climate conditions.

Goldenrod harvested from the mountain, photo by Sarah McPherson

“Everyone had tasks, like removing flowers from the goldenrod, stripping the bark from the alder, and crushing the charcoal sticks,” explains Carpick. The participants learned how to identify the wild plants and medicines to make goldenrod ink, speckled alder charcoal ink, and speckled alder charcoal sticks.

Goldenrod ink was made from the flowers, water, vinegar, and salt and then the mixture was simmered over a fire and strained. Carpick describes the product as a small batch, one-of-a-kind, living ink made directly from the land. “It’s about learning on a small level—forming a relationship that stays with you the rest of your life.”

- Preparing speckled alder harvested from the mountain to make charcoal sticks, photo by Sarah McPherson

- Elders and knowledge keepers preparing the goldenrod to make ink, photo by Sarah McPherson

- Goldenrod, speckled alder, and water from natural springs ready to make ink and charcoal sticks, photo by Sarah McPherson

- Removing the speckled alder charcoal sticks from the fire, photo by Sarah McPherson

Carpick also provided a handmade copper carbonate ink as a homage to the copper quarried by the Indigenous people of Kitchigami (Lake Superior). Using a template of the mountain and the hand-made, land-based art materials, each participant considered their relationship to Animikii Wajiw and created their own art.

Dr. Lindsay Galway talked about how people’s connection to the environment affects their health and wellness and artist and writer Sarah McPherson photographed the process, the artwork, and designed the billboard.

The participants talked about how nature is witness to the time we live in and how stewardship matters. They collectively agreed on an Anishinaabemowin call to action for the billboard: Animikii Wajiw manidoo bizindaw which means listen to Animikii Wajiw.

- Using a template of Animkii Wajiw on watercolour paper before painting, photo by Sarah McPherson

- Mountain keeper youth drawing with the speckled alder charcoal sticks, photo by Sarah McPherson

- Mountain keeper youth, Elders, and knowledge keepers with their completed artworks, photo by Sarah McPherson

“It’s really quite powerful to think about the mountain’s past, present and future,” says Carpick. “We listened, explored, and learned from Animikii Wajiw, nature, and each other. Individually and collectively, each artwork made with land-based inks and charcoals speaks to how knowledge building, stewardship, and being a good ancestor ripples forward.”

The billboard will be up until December 5, 2022.

Betty Carpick is a land-based artist, educator, and environmentalist. The interdisciplinary and intergenerational ways that she offers stewardship of land and water are shaped by her Cree and Eastern European heritage. For more information on her work, visit her Instagram page @bettycarpick or Facebook page @betty.carpick.