Remembering the Legendary Marathon of Hope

By Susan Goldberg

Forty years ago, Geoff Davis got a call from the emergency department at Thunder Bay’s Port Arthur General Hospital.

“Terry Fox phoned,” the nurse on duty told the newly minted family physician, on call over the Labour Day long weekend in 1980. “He wants you to go see him at his hotel room.”

Davis recalls walking into Fox’s room at the Prince Arthur Hotel, his medical equipment discreetly stowed in a brown paper bag so as not to attract attention. “Terry was sitting on the bed, silhouetted by the Sleeping Giant through the window behind him. And he looked up at me and said, ‘It’s back.’”

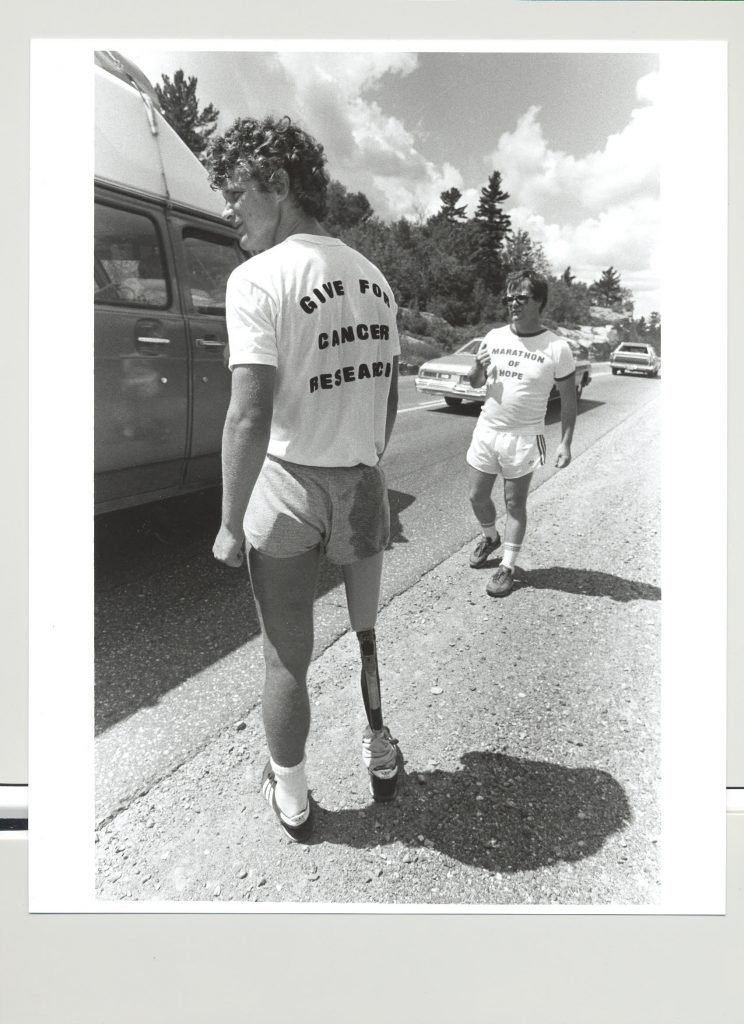

The “it,” of course, was cancer. Osteosarcoma had claimed Fox’s right leg in 1977, an experience that ultimately inspired his now-legendary Marathon of Hope. In April 1980, Fox, a 21-year-old from British Columbia, dipped his prosthetic leg in the Atlantic Ocean and then set off to run across Canada—the equivalent of a marathon a day—in order to raise funds for cancer research. At the time, his audacious goal was to raise $24 million: one dollar from every Canadian. Today, more than $800 million has been raised in Fox’s name for cancer research, according to the Terry Fox Foundation.

Just outside Thunder Bay, though, Fox faltered. “It was the last thing we expected,” says Bill Vigars, Fox’s PR manager at the time. The two had become close friends over the course of the Marathon—Vigars’s two children, Kerry Anne and Patrick, travelled with Fox and his crew across eastern Canada. Vigars, who’d taken the weekend off to see family in southern Ontario, panicked when the Ontario Provincial Police told him they couldn’t find Fox. After Terry finally called from a hospital payphone, Vigars talked his way on to a full flight from Toronto to Thunder Bay in order to see his friend. He arrived at the same time as Fox’s parents, Betty and Rolly, and the three went to the hospital together.

“Rolly kept repeating, ‘This is not fair.’ And Terry told him, ‘Dad, I’m no different than anyone else. This is what happens to people with cancer. Maybe now people will understand why I was doing this.’”

Dr. Davis—who’d spent an emotional weekend with Fox and his family—flew with Fox on the OHIP-chartered flight back to BC. His time with Fox cemented his decision to go into palliative care, he says. “Palliative care is really about adding life to the days that you have, not about dying. And Terry brought death out of the closet.”

Vigars remembers hugging Fox on the tarmac. “I said, ‘I love you. I’ll make you live forever.’ And then he left, and we were devastated.”

Vigars was instrumental in the design of the Terry Fox monument that pays tribute to the Marathon of Hope, just outside Thunder Bay. He still travels the world to speak about Fox and raise funds for cancer. On a recent trip to China, he spoke at a Terry Fox run. “I looked out at a sea of 8,000 Chinese teenagers, all wearing Terry Fox T-shirts. Never in a million years would Terry have imagined the impact he had, not only in Canada but worldwide.” Vigars—whose grandfather Richard Vigars, served as mayor of Port Arthur in 1905—had plans to travel to Thunder Bay this summer to commemorate the Marathon’s 40th anniversary. COVID-19 has cancelled those plans, but Vigars vows to make the trip as soon as it’s possible.

And while the Marathon of Hope’s 40th anniversary occurs during the coronavirus pandemic, Davis—now chief of staff at St. Joseph’s Care Group—reminds us that the Marathon of Hope also began in a pandemic, around another highly misunderstood condition. In the early 1980s AIDS was ravaging communities and sparking worldwide fear. “Nobody understood how contagious AIDS was. Physicians were petrified of having AIDS patients in their care. The rules kept changing. And in the general public there was a lot of fear—at its height, six people were dying a week in Thunder Bay.”

Today, Dr. Davis is still influenced by Terry Fox. “In my practice, I tell people, ‘I’ll never tell you that there is no hope. Even when you’re dying, there’s always hope for something a bit better. And Terry embodied that.”